These are some thoughts in response to an article by Larry Lavender Predock-Linnell and Jennifer Predock-Linnell, From Improvisation to Choreography: The critical bridge, Research in Dance Education, 2:2, 195-209. A link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14647890120100809.

I felt inspired to share a few of my thoughts about their article because I feel that the authors have limited notions of the possibilities of improvisation.

- “composing in the sense of shaping and forming movement material, and criticism—observing, describing, analysing, interpreting, evaluating, and revising both the work in progress and the completed dance.”

- The authors quote Nora Ambrosia – “‘Improvisation and creative movement are two dance genres that do not necessarily require participants to have a background in dance technique. … These two genres are focused on self-expression and self-exploration’ (p. 87).”

- and this – “… that improvisation exercises do not sharpen students’ awareness in any lasting way either of their own aesthetic values or those of others, nor do they compel students (mentally or physically) to exercise and test their ideas about dance as art.”

Did the authors ever think to question their method of improvisation pedagogy and what exercises they used? I would say that improvisation affords the dance maker plenty of opportunity to test ideas about dance as art, by allowing her/him to simultaneously compose and critique work. Improvising in the studio also has the benefit of having an audience, i.e., adrenaline, thereby creating a situation that is more similar to an actual performance.

- “In short, improvisational work…generally does not develop in students the kind of critical consciousness that we think is imperative to their future success as choreographers.”

– see the point above

- “while the dance world (particularly in academia) has long been deeply invested in promoting the idea and value of self-expression…”

This quote to me shows one thing that is wrong with dance education. It is seen as having an end goal, not as a means for knowledge production or investigation. What professor of structural engineering or radiology would say that they are invested in promoting the idea and value of self-expression? Who wants a dentist that went into dentistry for self-expression?

- “dance—rooted in bodily experience, and committed to the idea of the body as expressive of the range of human feelings and emotions”

This is another example of limiting the possibility of what dance can be used for. I am not denying that dance can be used to express the range of human emotions, but there is so much more.

- “Because we think they should, we argue that pre-choreography training—i.e. training in improvisation…”

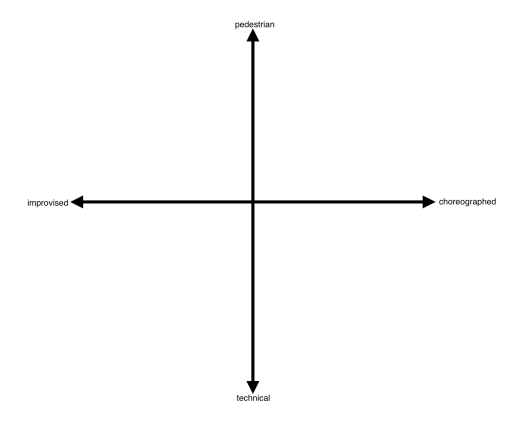

I would say that choreography can be used as pre-improvisation training. Choreography can be used to get a dancer out of habits of movement, as can improvisation (Re: Chaos dancing, fussy, neuro, etc). Both temporalities can inform each other.

By viewing improvisation as being in service to choreography, the authors, to quote Foucault, treat choreography as the “as the primary law, the essential weight of any” dance making practice. The authors attribute certain values to a relationship of time and unnecessarily limit the uses of dance and dance improvisation. They also have not investigated/questioned/problematized their relationship to and use of improvisation enough.